In 1948, the Texas Legislature recognized the need to keep records of motor vehicle fatalities when it passed a law requiring Texas coroners to report all traffic fatalities to the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS). But when Becky Davies, research scientist with the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI), began investigating alcohol-involved traffic fatalities in 1995, finding reliable data on blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) proved difficult. The records from the Texas Accident Database, established in 1975, contained only minimal identifying information for attempting to obtain missing BACs. With only the county where the crash occurred, the age and gender of the deceased and the date of death to use in the search, Davies’ role as an investigator took on a new dimension.

“I felt like Sherlock Holmes at times,” admits Davies. “I had to track down data from hard-copy files in medical examiner (ME) offices around the state. I reconciled the state’s minimal data with ME records to find out whether alcohol was a factor when those people perished in the crashes.”

There are several reasons why it’s so hard to find data regarding alcohol-related deaths. First, the original 1948 law was vague, failing to require what data elements to capture. Second, the law was never updated when, in 1955, the new system replaced the outdated coroner system in Texas. And third, many of those officials who were required to report the data were entirely unaware of the law.

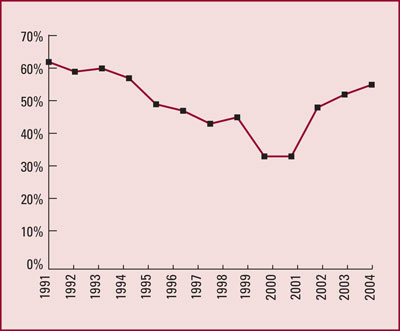

To help increase awareness of the BAC-reporting problem, TTI’s Center for Transportation Safety held workshops in 2002 and 2003 that brought stakeholders in the process together. The center’s efforts helped BAC reporting increase by 66 percent—from 33 percent in 2002 to 55 percent in 2004. Still, that means that nearly 50 percent of reports of fatalities involving alcohol fail to include BAC levels in the data collected.

“This is why TTI’s Center for Transportation Safety exists,” explains Dave Willis, then center director. “By bringing together different agencies sometimes isolated by bureaucracy, as these workshops did, safety can be significantly improved.”

The network for reporting traffic fatalities in Texas is complex. Law enforcement officers at the scene gather information about the crash, but often fail to report the BAC results. There are 13 ME offices in 15 counties; 900 justices of the peace (JPs) in the remaining 239 counties; and one DPS Crash Records Bureau. For the 36 percent of fatalities that occur in a county with an ME office, the body is transported for autopsy and toxicology screening. The other 64 percent of crashes occur under a JP’s jurisdiction, and often the JP does double duty as county coroner. Whether or not a body is autopsied and screened for a BAC level often depends on the county funds available.

In 2006, Davies was awarded an interagency contract from the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) to study this issue. A survey revealed that 53 percent of JPs were unfamiliar with the reporting requirement, and 28 percent didn’t even know such laws existed. Additionally, some 62 percent of ME offices failed to comply with the law. Davies enlisted a number of allies from around the state, including Sarah Kerrigan, forensic toxicologist, and Kim Frazier, lead coder for NHTSA’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) at DPS. The study’s results helped inform concerned lawmakers, and House Bill 423—which clarifies reporting responsibilities and requirements—passed the Texas Legislature in June 2007.

“The purpose of HB 423 is to ensure that policy-makers have the necessary data to implement measures to save lives,” says Texas State Representative Frank Corte.

Why all this concern over BACs and data collection? Improved reporting means better data. And better data can be used to develop better countermeasures to discourage driving after drinking. Moreover, the means to evaluate the effectiveness of those countermeasures will also be improved with reliable data. Though the left side of the equation is complicated, the right side is fairly simple: lives can be saved if people can be deterred from drinking and driving.

“Texas is very fortunate to have the strong partnership between TxDOT and TTI,” observes Judy Allen, TxDOT’s alcohol programs manager. “This effort provides another example of how our teamwork can improve safety for Texans.”