In recent years, there has been a boom of energy-related activities in Texas. While these efforts enhance the state’s ability to produce energy reliably, many short- and long-term impacts on the state’s right of way and infrastructure are not properly documented.

The Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) recently completed a project to document some of these impacts.

“The purpose of the project was to measure the impact of the increased level of energy-related activities on TxDOT’s right of way and infrastructure, develop recommendations to reduce and manage TxDOT’s exposure and risk resulting from these activities and develop recommendations for potential changes to business practices,” says TTI Senior Research Engineer Cesar Quiroga.

“Pavement was a big part of the project for the researchers,” says TxDOT project director Dale Booth. “The researchers focused their efforts in Abilene, Lubbock and the Dallas-Fort Worth area. And they found quite a bit of distress in those areas related to those industries.”

The researchers focused on the infrastructure impact by heavy trucks and machinery moving in and out of oil and gas well sites, as well as wind farms. Some of the problems observed included the following:

- Failures, surface ripples;

- Tire tracks on unpaved shoulders;

- Drainage problems at driveways;

- Mud tracking,

- Alligator cracking,

- Shoulder patches,

- Cracked seals; and

- Loss of surface.

The researchers also collected ground penetrating radar (GPR) and falling weight deflectometer (FWD). Considering the increasing level of activity in connection with the Eagle Ford Formation in South Texas, the researchers also met with officials from the Laredo, San Antonio, and Yoakum Districts.

“After we gathered the data, we conducted an evaluation of impacts of energy developments on the transportation infrastructure, including pavement impacts and remaining pavement life, roadside impacts, operational and safety impacts, and economic impacts. We also developed file geodatabases of relevant energy and transportation-related datasets and provided TxDOT with recommendations on how to alleviate potential problems that may arise with energy-related activities,” says Quiroga.

Critical recommendations at the end of the research included the need to maintain the geodatabase of energy developments to help TxDOT forecast and manage future developments, the need to engage and coordinate with energy developers earlier in the process and the need to strengthen certain protocols and requirements (e.g., those dealing with triaxial design checks, cross sectional elements on rural two-lane highways, and driveway permits).

“As energy development continues in our state, especially in the gas-bearing shale formations which have become so busy in the last ten years, having statistical basis to show their impacts serves as a springboard for additional funding,” says Booth.

Booth also notes the importance of the geodatabase as a communications and predictor tool for TxDOT.

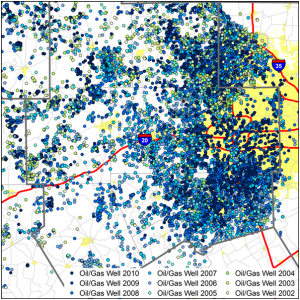

“As a communications tool, it is a visual way to predict well permits and well development in any area. When you run the program year-to-year, you can see ‘waves’ of wells progressing across the screen,” says Booth. “If you then show your audience the pavement distress and how that has progressed through the years, it paints a vivid picture of what energy developments in our state are doing to our transportation infrastructure. As a communications tool and predictor of future needs, the geodatabase is the centerpiece of this project.”

For additional information about this project, read the project summary report or watch the video summary report: Energy Development and TxDOT ROW.