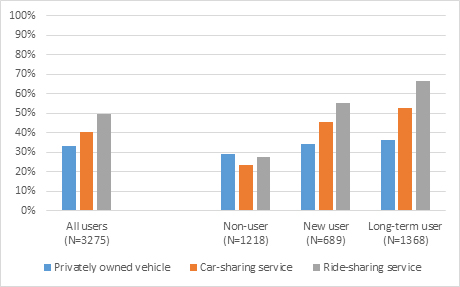

(The four group descriptions — all users, non-users, new users, and long-term users, illustrate how often the survey respondents use ride-hailing services.)

The latest research on consumer attitudes of automated travel suggests that frequent users of ride-hailing services are more likely to also use self-driving cars as they become more available, though many aren’t necessarily planning to own one.

The findings are instructive for emerging industries, researchers say, because the size of the ride-hailing market in a city provides a good estimate of the likely size of the early self-driving market, the characteristics of ride-hailing users define characteristics of early users of self-driving cars, and their travel patterns can inform how the services will impact an area.

The study, sponsored by Lyft, is based on a survey of 3,275 people in Boston, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and San Francisco/Silicon Valley, cities where self-driving vehicles are now being tested on public roads. The analysis was done by researchers at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

Ride-hailing services, also known as transportation network companies (TNCs), emerged in the late 2000s, using smartphone apps to connect passengers with drivers who use their private vehicles to provide rides for a fee. Although the young industry is still evolving, TNCs have generally found their market niche in urban areas.

Self-driving technology has advanced rapidly in recent years, but the costs and benefits of the technology are still being discovered. Those impacts will depend a lot on how and when the vehicles will be used, something that will be shaped largely by early adopters – those people who tend to start using a technology as soon as it’s available.

“If you’re one of those who lined up early on the first day that the iPhone 10 was available (whether you really needed one or not), you’re more likely to be among the first people lining up to use a self-driving car,” says Johanna Zmud, a study author. “Similarly, if you’re a frequent TNC customer, you’re more likely to be among the first who routinely use a self-driving car.”

Those early adopters are typically: aged 18 to 34, evenly split among males and females, middle-income, without children, without a vehicle or in a one-vehicle household, and, currently very aware of self-driving vehicles.

Overall, nearly 60 percent of respondents indicated an intent to use self-driving cars in some form. Intent was about 40 percent for non-users of ride-hailing users, 60 percent among new users, and 75 percent among long-term ride-hailing users.

Respondents preferred shared mobility services over private ownership of a self-driving car. About 50 percent preferred self-driving cars as a feature of a ride-hailing service; 40 percent preferred them in the context of car-sharing services (in which cars are rented for short periods, usually by the hour); 33 percent leaned toward private ownership. Researchers see several reasons for the inclination against private ownership.

Sensors needed to enable self-driving technology are expensive, but the cost is less of a barrier for fleet vehicles because they can generate revenue throughout the day while private vehicles do not. Testing results of self-driving cars on public roadways will need to be certified as safe before potential users and policy makers give a green light to wider use, something that will take many years to achieve. And, early uses of highly automated cars are likely to be geographically limited, so buyers are unlikely to invest in a car that can’t go anywhere its owner wishes to go.

Manufacturers and service providers face other obstacles as well, researchers say – not the least of which is that safety concerns and lack of trust in the technology remain barriers to owning or using self-driving cars. The Tempe, Arizona incident in March in which a self-driving car was involved in a pedestrian fatality – the first known death of a person struck by an autonomous vehicle on a public road – is one example.

“The competition to commercialize self-driving technologies must be balanced with the need to be completely satisfied – through robust research and testing – that the technologies are as foolproof as possible before their commercialization on public roadways,” Zmud says.

Texas is one of several states named by the federal government as a proving ground for that research, involving both test tracks and designated urban and rural roadways for real-world evaluation of self-driving technology. The Texas Automated Vehicle Proving Grounds Partnership includes TTI, the University of Texas at Austin, and Southwest Research Institute.