During the 1930s, several states proposed laws to prohibit the use of radios while driving. According to automobile historian Michael Lam, “Opponents of car radios argued that they distracted drivers and caused accidents, that tuning them took a driver’s attention away from the road, and that music could lull a driver to sleep.”

While technologies have evolved — substitute cell phone for radios in the above scenario — the central issue of how humans react to and behave in their driving environment remains the same. Human-factors research involves both cognitive and ergonomic factors, according to Senior Research Scientist Sue Chrysler, the Texas Transportation Institute’s (TTI‘s) current human-factors research program manager.

“‘Human factors’ is an umbrella term for several areas of research: human performance, technology design and human-computer interaction,” explains Chrysler. “It’s important for all driver communication — from the simplest traffic sign to the latest high-tech gadget.”

Chrysler’s group is involved in research projects across the entire breadth of human-factors topics, including “distracted driving.” This hot topic today represents the same concerns raised by opponents of car radios some 80 years ago — how drivers balance interacting with technology while keeping their eyes on the road and their minds on driving.

The idea that culture itself drives human behavior has recently made its way into human-factors research as well. “People are driving more and faster these days,” explains TTI Senior Research Engineer Shawn Turner. “The culture is one of being time conscious. That’s where you have people reading the paper or checking their e-mails while sitting in traffic or at a red light.” Turner’s research has focused on bicycle and pedestrian issues: improving pedestrian safety at unsignalized roadway crossings, updating the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA‘s) university course on bicycle and pedestrian transportation, and conducting the international scan of pedestrian and bicyclists safety and mobility in Europe.

Though numerous roadside safety innovations over the past half-century have made a huge difference in savings lives, John Mounce, director of TTI‘s Center for Transportation Safety (CTS), thinks those were the “easiest” improvements to make.

“Too many drivers think it’s their right to drink alcohol, text or be aggressive behind the wheel. It seems to be part of our culture,” acknowledges Mounce. “In human-factors research, we’re talking about creating a safety culture — a recognition of personal responsibility related to behavior and promoting traffic safety in each and every one of us.”

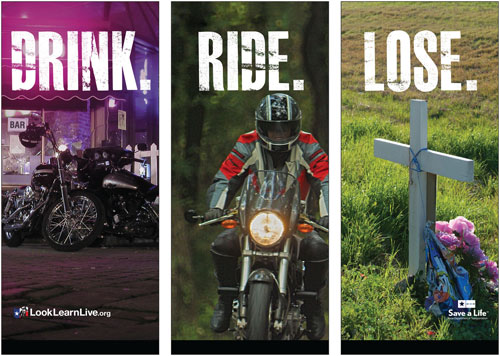

To encourage this behavioral change, CTS has teamed with the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) and the Texas Department of Public Safety to develop a new statewide motorcycle safety awareness campaign. “Someone dies nearly every day riding a motorcycle in Texas,” says Carlos Lopez, former director of TxDOT‘s Traffic Operations Division and currently the engineer for the Austin District. “Educating both motorcycle riders and drivers is essential to improving motorcycle safety and saving lives.”

Teens in the Driver Seat (TDS) is arguably TTI‘s most successful program dedicated to behavioral change — in this case in teen drivers. An in-school, peer-to-peer program that focuses on the principal causes of teenage fatalities, TDS has been implemented in 300 Texas schools and is spreading to other states. Research has found that awareness of the common crash risks for teens (nighttime driving, speeding and distractions) improved 40 to 200 percent at schools with TDS programs. Seat-belt use increased an average of 11 percent, and cell-phone use/texting dropped 30 percent. In 2009, TDS was given the Roadside Safety Award by FHWA and the Roadway Safety Foundation for its work with teens.

In the future, human-factors research will evolve along with the driving public. “By 2020, 20 percent of the population will be over 65, so issues with the elderly will drive our future research,” says Chrysler. “But that’s only one area we know of — there are others we haven’t yet begun to imagine. This is an all-encompassing and evolving field of research.”

Commentary on Human Factors

Paul Green

Past President

Human Factors and Ergonomics Society

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most things were built by hand. If a farmer needed a plow, he or she made it himself. The finished handle fit his hand because he designed it to fit, and over time, as the farmer’s needs changed, he could change the design of the plow. However, that personal touch was lost when the assembly line automated production, shifting the focus from user needs to the most cost-effective, timely way to make the product.

This was true across all industrial sectors, including transportation. Ralph Nader’s 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed revolutionized automobile safety by highlighting an industry’s seeming disregard for vehicle safety. That book and related activities spurred the funding of automotive safety research, the development of university research programs, and the passage of government regulations promoting safety. An important theme of that work was assessment of the human element.

Founded well before the Nader era, the Texas Transportation Institute (TTI) represents forward thinking by the Texas Highway Department and Texas A&M University. Quite frankly, for any question about driving and road design, TTI has always been the go-to place. TTI‘s leadership in national organizations, such as the Transportation Research Board, demonstrates the Institute’s unwavering commitment to research excellence and application in a world that, all too often, focuses only on the promise of the next quarter.

In the future, TTI will continue solving the transportation problems we face — dealing with even more road congestion, finding ways to reduce transportation-related energy needs, and introducing new systems to automate driving and enhance safety. Even the most automated systems have a human being as a vital component. Thus, human-factors research will continue to be essential. A particularly important challenge for the future is to develop the next generation of human-factors engineers and scientists to address these issues — something TTI and Texas A&M are well positioned to do through their partnership.