The intersection of transportation and health is a place where ironic and dissonant circumstances often collide.

- A driver whose life was nearly ended in a crash with one motor vehicle will typically depend upon another motor vehicle — a hospital-bound ambulance — to save his or her life.

- A person chooses to walk or bike to work or for recreation in part for health benefits, even as he or she takes on added health risks through exposure to cars and trucks zooming by alongside.

- A child with asthma depends on a car or bus for transport to a routine medical checkup, riding in a vehicle spewing toxins that exacerbate the need for such checkups in the first place.

These are just a few of the recognized ways in which the interests of transportation and public health jointly occupy a somewhat paradoxical space. Health care and health-promoting activities often depend on access to vehicular mobility, even as vehicular collisions and emissions constitute significant public health threats. However, the detrimental health impacts of transportation aren’t limited to crashes and traffic-related air pollution, as a new effort from the Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI) is demonstrating.

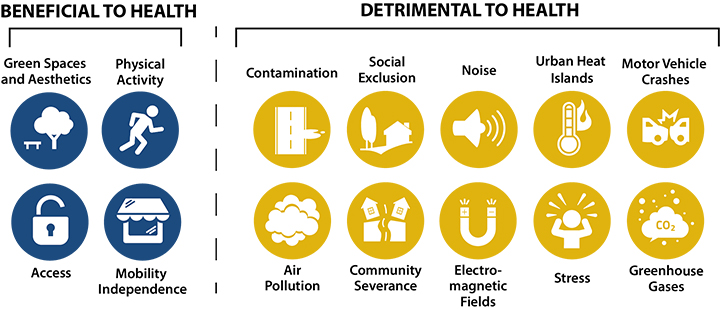

Researchers with TTI’s Center for Advancing Research in Transportation Emissions, Energy, and Health (CARTEEH) — a U.S. Department of Transportation University Transportation Center — have introduced a new analytical model. It outlines 14 pathways tying transportation to specific health outcomes — four of which are beneficial, and ten of which are detrimental.

Illustrating those connections is important because it helps to break down research and practice silos that can impair problem solving, says CARTEEH Director Joe Zietsman. He says a broader and more inclusive perspective can lead to understanding how transportation’s impacts on health involve complexities that reach far beyond the end of a tailpipe.

“Our purpose in developing this framework is to guide future research and practice toward more integrated and systematic assessments of transportation and health,” Zietsman says. “The factors we illustrate in this model represent distinct and separate pathways, but they converge in many ways because of their interdependencies — and that helps us to evaluate their impacts on health more holistically.”

Scientists have been exploring the transportation/health nexus for more than a quarter century, but CARTEEH’s latest foray represents the most expansive effort to date, Zietsman says. The new model branches out from four factors underlying transportation:

- land use and the built environment,

- infrastructure,

- mode choice, and

- technologies and disruptors.

The 14 pathways represent either beneficial or detrimental contributors to health outcomes, influencing either the cause or prevention of morbidity or premature mortality. Either set of pathways can be impacted by extrinsic and intrinsic factors, such as socioeconomic status, ethnicity, age and nutrition.

Efforts to quantify some of the pathways have already revealed their significant impacts on health, but that’s not yet the case for all of them. The costs of vehicle crash deaths and injuries are well documented, for example, as are the morbidity costs related to physical inactivity and air pollution. However, some of those pathways more recently identified by CARTEEH — such as electromagnetic fields, contamination and stress — lack enough data to thoroughly demonstrate their impacts. The new framework aspires to fill that need and to answer health/transportation questions that have yet to fully unfold.

Take the emergence of self-driving cars, for instance. Do new and disruptive technologies carry with them any unintended consequences for human health?

“Autonomous and connected vehicles rely upon the transmission of nearly constant electromagnetic field radiation in close proximity to the people riding in those vehicles,” explains TTI Assistant Research Scientist Haneen Khreis. “Emerging research indicates an association between those signals and adverse health effects, but so far, those connections haven’t been reliably measured. Our model highlights these associations and prompts researchers and practitioners to better consider them in a way that ultimately promotes holistic solutions that enhance the beneficial health impacts of transportation while mitigating its detrimental health outcomes.”

CARTEEH researchers are currently building on their new framework and expect to publish their expanded insights in a paper later this year.

“These areas warrant future research,” Zietsman says. “Our framework provides the basis for a systematic and well-rounded approach, and underscores the need to integrate human health into urban and transport planning and policy.”