By Dennis L. Christiansen, P.E.

Agency Director, Texas A&M Transportation Institute

Had the Texas Lyceum met at a conference to discuss Texas infrastructure a little over 100 years ago, say in 1911, the need for roads and “getting the farmer out of the mud” was a major agenda item. Had the conference met about 70 years ago, we would have discussed how to develop and rebuild a Texas infrastructure system that deteriorated during World War II. And had the group met about 55 years ago, we would have discussed the developing interstate highway system. But today our strong state economy and burgeoning population growth have made our transportation challenges perhaps more daunting than ever. How did our modern-day Texas transportation system develop, and where do we go from here?

Mid-20th Century Super Roads

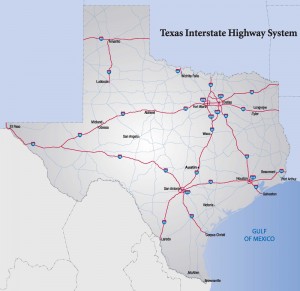

Texas began constructing freeways in the late 1940s, and those roads, along with the early Texas interstates, provided massive increases in roadway capacity. President Dwight Eisenhower signed the interstate highway bill in 1956, establishing not only a systems approach and a design concept, but also a financing mechanism. The country had an interstate highway program, a federal gas tax and a Highway Trust Fund, all of which truly changed Texas and the nation.

Indeed, it appeared the state was designing roads for lanes per vehicle instead of vehicles per lane. These super roads have served us well. With the migration to the Sunbelt, Texas attracted massive economic development and our population swelled. This new system of urban roadways accommodated a lifestyle desired by many Texans. Our citizens were able to live in houses on individual lots, drive on uncongested roadways, park right next to their destinations and buy inexpensive gasoline. For those who liked wide open spaces, Texas was the place to be.

The interstate highway system is a great example of the often cited relationship between transportation and the economy. Without the system, our state today would have 1.6 million fewer non-farm jobs, which would support a population of 4.2 million fewer people. If anything, these roads may have served us too well—our roadway system and funding mechanisms have been so good they have allowed us to defer meaningful decisions on what comes next, and how we pay for it.

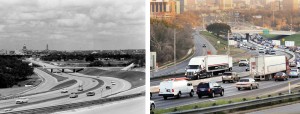

However, the days of the uncongested lifestyle have changed significantly. Today, actual volumes per lane on Texas freeways are more than twice what was originally planned. Typical volumes on Houston freeways are 70 times larger than they were in 1936, and 10 to 50 times greater than in 1960. We have lived for decades off of the transportation capacity we developed from about 1960 through 1980. But as the 20th century wound down, we began building less infrastructure, while the growth in population and travel continued.

21st Century Congestion Challenges

Given existing congestion in Texas and the expectations we have for future growth, we obviously have very real transportation-related problems. We should not be surprised that once again, just like in 1911, transportation was a major topic in our legislature in 2013. Let me make a just few points to help define where we are today.

First, keep in mind that everything about congestion is not bad, as congestion is a byproduct of economic prosperity. Other cities have “solved” their congestion problem by tanking their economies, an approach we certainly don’t want to follow.

Second, the Texas population will continue to grow, and the characteristics of that population are changing—it is becoming more urbanized, older and more ethnically diverse. This topic could be an article all by itself, but suffice it to say that the growth and the changing characteristics of our population have profound impacts on the transportation system.

Third, and not surprisingly, congestion in Texas is bad, is growing rapidly and will continue to increase. In our largest cities the rate of growth in congestion is in excess of 8% per year. In 2012, the total cost of congestion—delay time and wasted fuel—exceeded $10 billion in Texas. A typical auto commuter in Austin, Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston, wastes well over 40 hours per year stuck in traffic—time not spent with family and friends. The amazing amount of attention that TTI‘s annual Urban Mobility Report receives reflects the national interest in mobility and congestion.

Over the past 40 years, our population has more than doubled – up by 125 percent. The number of cars and trucks on the road has almost tripled. And the number of miles those cars and trucks travel has more than tripled. Over the same time, our roadway capacity has grown only modestly—by 19 percent. We have too much demand for roadway space and not enough supply. It’s that simple.

So, with these challenges as background, where might we be headed?

What’s Next and How Do We Pay?

Much of the discussion in the 2013 session of the Texas Legislature focused on how to fund infrastructure through the Texas Department of Transportation. The state and federal gasoline tax, our primary revenue sources, have not been indexed to inflation and have not increased in 20+ years. The 20 cent state gas tax we had in 1991—the last time it was increased—now buys only 9.2 cents of road construction. Increasing fuel efficiencies and use of alternatively powered vehicles simply compound the problems associated with the gas tax. What does this mean to the average Texan’s pocketbook?

The average Texan pays about $10 per month in state gasoline taxes for the roads we drive on every day. Compare that to the typical monthly cell phone bill today. Similarly, I pay more than four times as much to park my car on the Texas A&M University campus than I do to drive on the state’s roadway system, although most of my trip to this parking space is on state roadways.

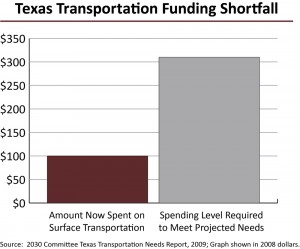

In 2008, the chair of the Texas Transportation Commission appointed a blue ribbon committee, named the 2030 Committee, to look into transportation needs and funding in Texas. The committee made a number of key findings, one of the most significant of which is shown in Exhibit 3. Simplistically, if all we want to do is keep congestion at levels similar to what we are experiencing today and maintain our infrastructure in about the same condition as it is today, our current funding sources will provide only about one-third of the money the state needs.

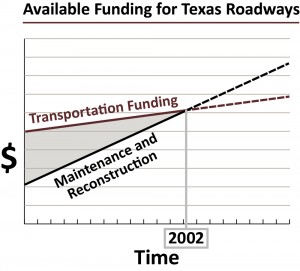

Exhibit 4 shows conceptually the funding required for maintenance and reconstruction of state roadways and available funding. Over time, as more miles of roadway come on line and those facilities age, the curve slopes up. As long as the revenue stays above this curve, there is money to build new capacity, so the question becomes when do the lines cross? The data indicate we actually ran out of money and the lines crossed in 2002—more than a decade ago. We have been able to keep building in part because Texas has moved to more aggressive toll road development.

But we have also poured a lot of one-time funding into the system, most of it associated with bonding. Between issuing bonds to pay for infrastructure and using federal stimulus money, over the past dozen or so years, we have added nearly $25 billion in one-time cash infusions into the transportation system. As many members of the legislature will say, we have “maxed out” our credit card. We have debt to pay off, and the one-time funding that we received does not provide the funds needed to operate and maintain these facilities.

In addition, the infrastructure we are building is becoming increasingly expensive. Highway projects costing more than $1 billion and expensive transit projects are part of the mix in today’s world. The price tag on the rebuild of North Central Expressway in Dallas was $60 million per mile; the Katy Freeway in Houston cost $100 million per mile. Light rail construction in Houston and Dallas cost about $75 million per mile.

So it is appropriate that the Texas Legislature is devoting, and will continue to devote, considerable time trying to come up with an approach that can provide significant, predictable transportation infrastructure funding looking to the future.

It’s Not Just About Infrastructure

But while building more infrastructure has been extremely beneficial in making Texas attractive for economic growth, it alone is no longer the total answer in the 21st century. This approach is simply not scalable as Texas continues to grow. Significant change must occur. We will never have all the funding required to build our way out of our current situation and even if we did, we do not have the space to build that capacity. And if we had the space, we could never obtain all of the required environmental clearances.

A successful 21st century transportation system will need to be different from what we have developed in the past. We will need to increasingly turn to other tools, and we began doing this over the last quarter of the 20th century through the use of developing technology and private sector entrepreneurship.

There is no silver bullet to solve all of our transportation problems. We must use our infrastructure funding to add capacity where we can get the most “bang for the buck” – in critical corridors and to enhance safety statewide.

We will need to leverage as much as possible from the present infrastructure. In effect, we need to operate the facilities we have in a more optimal manner. We must also manage demand by changing usage patterns and providing choices, such as telecommuting.

We have to do a better job of coordinating land use and transportation decisions, facilitating the use of modes other than highways—such as walking, transit and bicycling. Freight transportation and intermodal connections will be much higher priorities in the future. And we must coordinate our efforts as part of a comprehensive, systematic approach to providing a scalable 21st century transportation for Texas citizens.

In the domain of transportation, as in all aspects of human endeavors, the only constant is change. It is natural to consider the system of any current activity in which you are functioning to be the pinnacle of technical or scientific development—if that system is working for you.

Let me again step back in time to try to better illustrate this point.

It’s About World-Changing Technologies

Pretend you are walking along the coast of North Carolina on a cloudy, cold windy day. It is December 17, 1903. As you walk over the dunes at Kill Devil Hills, just south of Kitty Hawk, you come upon this amazing contraption. It has two wings and an engine designed using bicycle technology. And you see someone laying on one of the wings and holding on. As you stand there, this heavier-than-air machine goes airborne for all of 12 seconds. It flies 120 feet—less than the wingspan of a Boeing 707—and crashes.

What is your reaction? Probably something along the lines of “that nut is going to kill himself.” But this clumsy 1903 flight literally changed the world. If you witnessed this flight in 1903, it would not begin to occur to you that 100 years later, airline passengers would be routinely flying from New York to Paris in six hours, or that an airline industry would be born and help create a global economy.

I suggest that new transportation technologies—world-changing technologies—will dictate the future of transportation. A decade ago, those of us who had cell phones used them to make phone calls and not much more. But think how much cell phone technology has already changed how we travel in just the last decade. Like 500,000 Houstonians do, you might go online to get real-time travel information, or you might access the appropriate app. You might sign up to receive text messages when an incident occurs that could interfere with your commute. The trucking company bringing you your goods likely uses the real-time data to more efficiently route its vehicles.

Extensive deployment of technology allows motorists and truckers now traveling through the 96-mile-long I-35 construction zone in Central Texas to be fully aware of travel conditions. Your car may have adaptive cruise control or collision avoidance systems. Or, you may have OnStar® or a similar system that provides automatic crash response, stolen vehicle tracking, turn-by-turn navigation and roadside assistance. Or maybe you have seen the Google car—no driver required.

Large-scale tests are currently underway with vehicles talking to vehicles through the internet. Tests are being set up where these vehicles will also talk to the roadway infrastructure. The potential safety and capacity benefits associated with these technologies are unbelievably huge. The large automobile manufacturers are spending billions of dollars researching these areas. Companies are developing technologies that can result in more convenient and efficient travel, such as fully interoperable toll facilities; parking space locators; or solar energy collected from roadways to power electric vehicles.

The Future Requires Our Attention

In 2013, our situation is similar to where the Wright Brothers were in 1903. Just think of where we will be when the Apple IPhone® “version 64” hits the market (although it will probably be a virtual phone). The futurists tell us we will travel when we need to get together, but not our for basic work day. We clearly won’t travel as much we do today, at least not in the same manner.

As we speculate about the future and what might change, let me again step back in time. In 1898, delegates from across the globe gathered in New York City for the world’s first international urban planning conference. Only one topic dominated the conversation. It was not housing, crime, technology, or even traveler-centric. The delegates were driven to desperation by horse manure.

By the late 1800s, the problem of horse pollution had reached unprecedented heights. In 1894, the Times of London estimated that by 1950, every street in the city would be buried nine feet deep in horse manure. One New York prognosticator of the 1890s concluded that by 1930, the horse droppings would rise to Manhattan’s third story windows. A public health and sanitation crisis of almost unimaginable dimensions loomed. But horses were essential for the 19th century city—without them, the cities would quite literally starve. Stumped by this crisis, the urban planning conference declared its work fruitless and adjourned in three days instead of the scheduled 10 days. Thankfully, another world-changing technology—the internal combustion engine—solved that particular problem.

Automobiles, airplanes, IPhones, whatever—we have not been very good at thinking about what is next. We continue to plan for the future assuming it will be just like the past and it never is. We need to re-think the way we are doing things. The 21st century transportation system requires the effective use of all the available tools, including existing and emerging technologies and multiple transportation modes. No state, region or city has yet figured out exactly how to put all of the tools together successfully.

However, the first state that finds the solutions to our 21st century transportation system will have a tremendous economic advantage. And given the existing transportation problems in Texas and our anticipated population growth, we need to be one of the first to figure it out.