When we talk about automating vehicles today, it sometimes sounds very futuristic. Relinquishing driving duties to a computer is a scary thought for some. But one thing to remember is that automating vehicles isn’t a new idea. It began over a hundred years ago with the notion of tying automation to safety.

You probably know that motorists used to start their cars with a crank inserted into the engine block and turned by hand. Then the electric starter came along. These days, cars start with the push of a button; you might even start up from a distance, before you’re even in the vehicle.

But do you know why the electric starter was invented? The story goes that in 1908, a good Samaritan named Byron Carter stopped to help a stranded female motorist. Carter offered to turn the hand crank to get her car started again. The crank kicked back (a common problem at the time) and broke Carter’s jaw. Eventually, his injury led to pneumonia and the illness killed him. His good friend, Cadillac founder Henry Leland, was devastated by the loss.

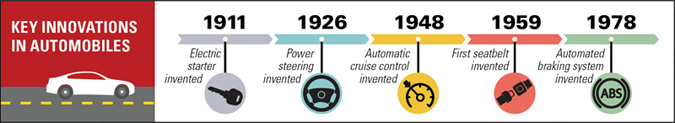

Leland vowed that simply starting a car would never kill another man. He hired Charles Kettering, who invented the first electric starter in 1911. The concept of marrying vehicle automation with safety was born.

The process of automating vehicles has accelerated significantly since then: power steering; automatic cruise control; automated braking systems. Besides making driving more convenient and efficient, these innovations have another, historically significant purpose: to improve safety for the vehicle’s occupants.

The private and public sectors are now working together to make connected transportation a reality in the very near future. In Michigan, for example, we’re enhancing technology in over 500 intersections in the southeast portion of the state to improve safety and operational reliability. That initiative demonstrates the essential equation of connected transportation: public agencies deploying privately developed technology for the public’s benefit.

A completely connected transportation network won’t happen overnight. But in the next decade, I see a dedicated freeway lane reserved for self-driving cars (similar to how high-occupancy vehicle lanes have developed). Eventually, that innovation will spread to all lanes, seamlessly connecting vehicles to infrastructure via constant communication. Once the network is completely automated, lane specifications — originally developed 60 years ago when cars had manual steering and motorists needed more time to make adjustments — will shrink, adding capacity without widening the roadway. And that will mitigate ever-worsening congestion and increase mobility. Safety will also improve as vehicles coordinate with each other and the roadside to avoid crashes often resulting from human error.

There are a number of challenges to getting us there. Policies that balance privacy with public good must be developed. Questions about how to secure data passed between vehicles and infrastructure against hackers must be answered. And how do we pay for the massive infrastructure refit to make it all work? Arguably, that’s the stickiest question of all.

Agencies like the Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI), with its international reputation for innovating infrastructure safety, are at the forefront of this process. It’s from the research findings and test beds of institutions like TTI that connected transportation will spring.

Our future — whether we’re speaking of transportation or anything else — is driven forward by innovation: in vision, in applying new technology and in the desire for progress. Whatever you think of your car driving you to the store, that reality is just around the corner. Getting us safely there by maximizing technology for the collective benefit of society is incumbent upon all of us in the transportation industry — public and private sector alike.