Austin is a modern, thriving city with a population that enjoys an active lifestyle, including the increased use of nonmotorized modes of transportation. Many appreciate the numerous benefits of active transportation, though the growing popularity of nonmotorized modes can also bring increased collisions involving pedestrians, bicyclists and motorists.

“Incidents like these aren’t as common as vehicle-to-vehicle crashes, but when collisions do occur, they’re more likely to end in serious consequences,” says Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI) Associate Research Scientist Ipek Nese Sener. “Preventing and reducing crashes involving active travelers are important goals for transportation authorities and agencies, as is mitigating injury severity.”

A recent research project conducted by TTI for the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) Austin District examined pedestrian/bicycle-vehicle collisions in the district for the purpose of developing the Austin District Bicycle and Pedestrian Crash Prediction Tool. As part of this effort, TTI researchers examined fatal, incapacitating and non-incapacitating crashes involving a vehicle and a pedestrian or bicyclist that occurred in the district between 2007 and 2014.

“This study aimed to develop four separate crash models to provide comprehensive insights into the contributing factors related to crash frequency and severity for different active travelers such as pedestrians and bicyclists,” notes Sener. “The models showed the important role of different variables in crash frequency and severity, including travel demand, commute behaviors, network characteristics and sociodemographic features. Using the model results, we identified areas of concern with the greatest potential for safety improvements.”

As might be expected, the core downtown Austin area was the location of most pedestrian/bicycle-vehicle collisions. When it comes to severity, the central business district of Austin ranked high in terms of observed severe bicycle and pedestrian crashes.

The model results indicate that the greatest potential for safety improvement lies in central Austin. In this area, Sener says, reducing crash frequency is more of an urgent focus than alleviating crash severity. For severity, there’s not one specific area of major concern. The efforts to mitigate crash severity are needed across the region.

“The study was useful in showing common contributing factors to severe pedestrian and bicycle crashes,” notes James Bailey, highway safety projects and railroad engineer for the TxDOT Austin District. “It’s led to TxDOT implementing district-wide safety improvements such as high-visibility crosswalks and traffic signal improvements.”

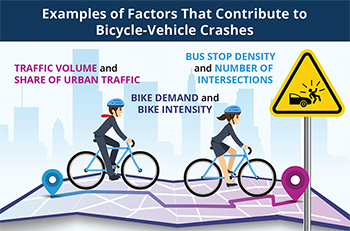

While many variables (e.g., traffic volume, walking mode share, percentage of principal arterial roads, and bus stop density) correlated with an increased (or decreased) probability of a pedestrian crash or bike crash, other variables played different roles in explaining pedestrian versus bike crash mechanisms. For example, factors like the percentage of minor arterial roads, network density, and sidewalk length increased the probability of pedestrian crash occurrences only. On the other hand, factors like the percentage of large urbanized traffic and number of intersections were positive indicators for increased bike crashes.

These variations might stem from inherent differences in travel patterns between walking and bicycling. The varying influential factors emphasize the need to differentiate approaches to deal with safety issues between the two nonmotorized modes.

“The study results can help develop safety improvement interventions for vulnerable road users in the Austin District and exemplify how other transportation agencies can estimate pedestrian and bicycle crashes using their existing database and crowdsourced data,” says Sener.