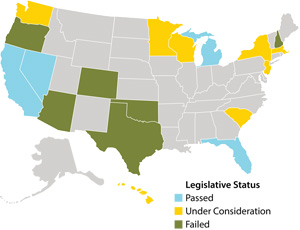

The widespread presence of self-driving vehicles is still many years away. To manufacturers, those years represent a long and anxious wait to get their products to market. Government decision-makers, on the other hand, might view the wait as a good thing, since they will need all the time they can get to work through the public policy aspects that go along with such a dramatic change in the way we get around.

Researchers at the Texas A&M Transportation Institute (TTI) recently examined those aspects in a study funded by the Southwest Region University Transportation Center — Automated Vehicles: Policy Implications Scoping Study. The work was conducted by TTI researchers Jason Wagner, Trey Baker and John Maddox, along with Ginger Goodin, director of TTI’s Transportation Policy Research Center. As part of the study, researchers interviewed both transportation agency representatives and vehicle manufacturers. Each party brings unique perspectives and responsibilities to the emerging world of automated vehicles.

“The private sector is responsible for developing automated vehicles, and the public sector has a part to play in making sure those vehicles operate safely on our infrastructure,” Goodin says. “At the intersection of those two roles, we have a number of policy-related questions that we need to answer.” In each case, those questions are directly tied to the substantial benefits that both industry and governments are counting on.

- If more sophisticated automated-vehicle (AV) infrastructure requires higher levels of maintenance, how can that cost be justified when agencies are already short on resources?

- If fully automated vehicles will require no driver involvement, how will traffic laws change, given that the laws are predicated on a fully engaged operator behind the wheel?

- If a vehicle operating in fully automated mode crashes, who assumes the liability — the operator or the equipment manufacturer? What is the infrastructure operator’s risk?

- What are the privacy, data ownership and security-related concerns associated with vehicle-generated data — which could be used for commercial or public purposes — including managing system congestion?

Benefits from AVs are possible but less certain. For instance, AV technology can allow vehicles to move more closely together in platoons, potentially reducing gridlock and improving safety. And if cars aren’t crashing, some safety features that we design into our roads — standard lane and shoulder widths, for instance — are no longer required, allowing agencies to reconfigure the right of way for more lanes. At the same time, AV technology may motivate travelers to make more frequent trips, which could actually increase roadway congestion.

No matter what, further study is needed to fully understand and measure AV benefits due to the high level of uncertainty surrounding the deployment of the technology.

“In an era of fiscally constrained public institutions, there’s a lot of pressure to justify the expenditure of public dollars,” Wagner says. “Without being able to quantify the benefits of AVs, public agencies will be less likely to invest in them.”