Episode Preview with TTI's Jim Kruse (audio, 29s):

Full Episode (audio):

Episode Detail

January 31, 2023Episode 50. Bent, But Not Broken: How global supply chains demonstrate post-pandemic resilience.

FEATURING: Jim Kruse

Most of what we buy and use every day comes to us on cargo ships, which represent essential links in worldwide distribution systems. A global public health crisis reminded us of how important they really are.

About Our Guest

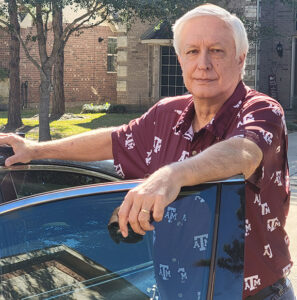

Jim Kruse

Director, TTI Center for Ports & Waterways

Jim Kruse is the director of TTI's Center for Ports and Waterways, a position he's held for 20 years. He's responsible for research involving waterborne freight transportation and its multimodal connections. He has been a port director and has served as the Marine Group Chair for the Transportation Research Board. Additionally, he served two terms as a member of the Marine Transportation System National Advisory Committee.

Transcript

Bernie Fette (host) (00:14):

Hello again. This is Thinking Transportation — conversations about how we get ourselves and the things we need from one place to another. I’m Bernie Fette with the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. During the Covid 19 outbreak, stories in the New York Times mentioned supply chains more than 45,000 times. Prior to the pandemic, you had to look pretty hard to find any mention of supply chains in mainstream news sources, and that doesn’t even count social media, where mentions increased by more than 10 times. During the lockdown, we couldn’t seem to get the things we needed when we needed them, and it was easy to blame the supply chains for our inconvenience. Our guest for this episode will help us understand why it’s not quite that simple. Jim Kruse is a senior research scientist at TTI and an expert in the freight that moves on cargo ships — the way that we get so much of the things that we use every day. He’s the director of the Center for Ports and Waterways at TTI. Jim, welcome. Thank you for joining us today.

Jim Kruse (guest) (01:30):

Thank you. I always appreciate the opportunity to chat with you.

Bernie Fette (01:34):

When the pandemic started, people had a very difficult time getting the things they needed, and the reason that we were given for that is that the supply chain was broken. So if we can, I’d like to start with a really broad question and then maybe try to narrow the conversation from there. My question is, is the supply chain still broken?

Jim Kruse (01:57):

Well, I’m glad you asked it that way because the way I look at it, it was never broken. It was overwhelmed. And to me, that’s a distinction, and I’ll give you an example of how that would work in real life. If you take a five gallon jar of water, like you have a water cooler and you just dump it in your sink all at once, your sink will back up and you’ll have water maybe coming out of the sink depending on how fast it drains. Does that mean your piping is broken? No. Does it mean you’ve got a problem with the plumbing? No. You just try to do too much too fast. Yeah, and I think that’s where our supply chain wound up. It wasn’t broken. It was never designed to handle the volumes we’re forcing it to handle.

Bernie Fette (02:34):

Okay. Really important distinction there. So if we take that distinction a step further and ask the question again, is the supply chain still overwhelmed, how might we get a different answer, depending on whether we are talking to shippers or if we’re talking to consumers?

Jim Kruse (02:54):

I think right now things have smoothed out quite a bit. Initially the problem was that there was such a surge in consumer buying that the volumes rolled like 23 percent in one year, which is just overwhelming. Right. Since then, things have leveled out a little bit. You saw these news reports about how many vessels were staying off the coast of California waiting to get to the port and that kind of thing. That’s gone away. Pretty much. Things are functioning pretty much like they should in an ordinary situation. So today that’s fine. But that being said, everybody expects another surge to hit at some point. And so what people are doing now is they’re buying equipment. Suppliers are spreading out their sources of materials and so forth that they’re not dependent upon one particular part of the world and things are happening. People are responding to this by setting themselves up for the next surge that it won’t be as bad as this last one was.

Bernie Fette (03:44):

So adjustments are happening. Some of ’em on their own and some of ’em by design. Of course, seaports represent a really prominent link in that supply chain that we’re talking about that’s been overwhelmed. And that’s your specialty area, I know. So can you give us a sense of how much of the stuff that we buy comes to us on cargo ships and how much of the stuff that we send away from America goes out on cargo ships?

Jim Kruse (04:10):

Well, as far as coming in goes, people would find it interesting. The largest importer of consumer goods in a containerized shipment is Walmart. Then you have Home Depot, you have Toyota, you have Lowe’s, you have all these brand name consumer places that we go to that are the big, big, big importers. So those are the ones who are making it happen. Exporting typically winds up being agricultural goods or in some cases even waste paper, waste products that are being processed elsewhere in the world. So that’s kind of how it comes and goes. I challenge people sometimes to go around their living room and look at where everything was made, and I think you’ll find that almost nothing was made in America <laugh>. Okay. So if it wasn’t made in America, it had to get here somehow. And you’re not gonna fly a couch on an airplane, you’re not gonna fly a table on an airplane. So those came on a boat from someplace. Your clothes came on a boat from someplace. I’ve often used the illustration, if you took out everything in your house that came on a boat and didn’t have any of it, you might be sitting there with no clothes on in the middle of an empty house.

Bernie Fette (05:15):

Right. And no bed to sleep on, et cetera.

Jim Kruse (05:18):

That’s right.

Bernie Fette (05:19):

Let’s talk a little about, cuz I think part of what you’re getting at is just the simple laws of supply and demand. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. Let’s talk about that just a little if we can. I’m wondering how the supply and demand trends may have changed, if at all, in recent years. And please answer that question if you could however you’d like. I mean, if you’d like to talk about post pandemic or were they already changing before the pandemic, please? However you’d like to address that.

Jim Kruse (05:46):

Well, trade was actually increasing before the pandemic, but what happened during the pandemic, two things happened. One is people said, well, I can’t travel. I can’t go anywhere, so I’ll just buy stuff for my house. I’ll buy computers, gaming equipment, exercise equipment, patio stuff. So they just started buying in tremendous quantities. In fact, there was a 23 percent rise in consumer buying from one year to the next, which is difficult for any kind of business to absorb. It was just a tremendous volume. The real problem was on the other side, when Covid first hit, people said, well, nobody’s gonna buy anything. We’ll just start closing our factories down. And all of a sudden people did start buying stuff and they weren’t ready to produce what people wanted to buy. So you had kind of a little bit of a shortage because the producers were caught unaware of this latent demand that hit them. The buyers were going crazy, buying everything they could get their hands on because they couldn’t do anything else with their money. And so these two things came together to overwhelm the system. And then we got these backups.

Bernie Fette (06:42):

So all of those producers you’re talking about weren’t considering the possibility that people were gonna take their vacation money and spend it on stuff. Right? Yeah. Which I think was a lot of what the news was, the news trends at the time where people were foregoing vacations because they couldn’t go anywhere. So they decided they had to have some outlet for their desire to spend their money.

Jim Kruse (07:01):

And the economic data we’re seeing now too, show that people have kind of slacked off on that consumer of buying and started spending it on travel and services again. And so we’re seeing more of a pre-Covid type of distribution of spending, which will help quite a bit in smoothing things out in the system.

Bernie Fette (07:17):

I think one of the points that you made earlier, the distinction of how the supply chains are being overwhelmed as opposed to supply chains being broken. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. Please correct me if I’m drawing too much of a parallel here, but can we not draw at least some comparison with surface transportation and the fact that you can’t build highways and bridges to handle surges all of the time, just because that’s not a very practical way to approach. Is there a legitimate parallel in what we’re talking about there?

Jim Kruse (07:45):

I think so. As you say, you can’t build for the potential peak situation because then you would have a lot of assets sitting idle most of the time and nobody can afford that. Yeah. On the other hand, if your system is set up to be agile and flexible, maybe you can reroute things, you can move things around. You can use alternate methods of getting things from A to B that would alleviate or mitigate some of this delay that we saw during the pandemic.

Bernie Fette (08:10):

Okay. So supply chains, again, not broken so much as just being overwhelmed. And you talked about how some of the consumer trends are helping to make adjustments to that situation of being overwhelmed. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. What else is happening on the, I guess the manufacturer, the shipper side of things to address that condition of being overwhelmed?

Jim Kruse (08:36):

Well, there are two major things I see happening. One is 40 percent of our goods or more come from China and they land on a West Coast port. A lot of those shippers now are rerouting their stuff through the Panama Canal over to the Gulf Coast and the East Coast to kind of spread out their network. Okay. So that if Los Angeles / Long Beach gets whammed all of a sudden they’ve still got an outlet to go somewhere. They’ve got an established system someplace else that they can use. It takes more time and it costs more money. So it’s gonna drive up the cost of goods a little bit, but at least the demand gets met. That’s the big thing. The other thing is that during the pandemic, one of the things we saw was that equipment was getting stuck everywhere you looked. Equipment was sitting idle. For instance, a vessel tries to come into the port of Los Angeles. They say, we’ve got all these containers to unload. The terminal says, well, I’m sorry, but we’re full. We can’t do anything with those. So they call the warehouse, they say, we’ve got some containers we need to send your way. And they go, well I’m sorry but we’re full. We can’t take any more containers and if you send any, we’re just gonna leave ’em in the parking lot cuz we can’t do anything with them. Then you say, well, okay, let’s put on a rail line, let’s get it out here on rail instead of by a truck. Well, the rail line tells you, well, all of our rail yards are full. We’ve got no place to put that stuff. But what happens is, if everything is sitting there waiting for an opening, you’re reducing the amount of equipment that’s actually working.

Jim Kruse (09:53):

And at one point we estimated there was 20 to 30 percent of our equipment that was doing nothing because it was sitting waiting because of a congested situation. So what people are doing now is they’re buying equipment like crazy. I mean, we’re seeing more cranes bought and these containers move on what’s called a chassis. It’s a specialized trailer that they sit on so they could be moved. People are buying a lot of those that they don’t have to worry about getting one to move a container. Warehouse space has just gone through the roof. It’s essentially 100 percent used in Southern California and in here in the Houston area. It’s also a huge demand for this warehouse space and it’s just going up like crazy. So what people are doing right now is they’re trying to set themselves up to have more equipment so that if another situation to happen where you’ve got 15 or 20 percent getting tied up someplace, at least you’ve got equipment to work with. You’re not stuck waiting on somebody to free it up.

Bernie Fette (10:43):

Okay. You’ve given us a good picture of how the industry and how some consumer habits are helping to level things a bit. Mm-hmm. <affirmative> Helping to equalize and, and maybe calm things down a little bit with such a huge increase in consumer purchasing. What are the supply chain fixes, if we can call ’em that, that still need to be addressed? The improvements that you think need to be made, but we’re not there yet.

Jim Kruse (11:10):

One of the big things that people are checking right now is the ability to hand information out between all the various parties involved. And I should back up a step. When we say supply chain, what we’re talking about is all the businesses, all the services, all the equipment that’s needed to get something from the point where it goes to a factory and that factory produces it, and then it comes over to the final consumer here in the U.S. All that’s part of the supply chain. One of the problems is that there is no single source of data that says, okay, I bought this. It’s coming out of Shanghai. Where is it? What ship is it on? When is that ship gonna get here? Where is it in the terminal? Once it gets off the ship, how do I know where to go get it? All these kinds of things. When is the ship expected to arrive, for instance? These things are not getting handed off between all the, the various players is there’s a big push right now. The federal government’s involved, several private parties are involved, but setting up a system where you can trade this information, where you can access information that tells you where things are, when big events are expected to happen, and allow you then to marshal your resources effectively.

Bernie Fette (12:10):

In maybe much the same way that you can go online and find out if that package that was mailed to you by a family member in another state, you can go to the right website and figure out exactly where that package is.

Jim Kruse (12:25):

Right. And the idea again is to provide some real-time insight into what’s going on with your delivery, but also to provide a little bit of a forecast method so that if I know that I’ve got a thousand containers are gonna hit me next month, I need to have the trucks in place, the warehousing space available, I need to have the chassis available, the people available, and I can plan for that. If I’m just sitting here and a thousand boxes show up, uh-oh, what am I gonna do now? <laugh>. So that’s kind of the idea behind all that.

Bernie Fette (12:53):

Yeah. Try to minimize the surprises. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. We as consumers, were really not talking about supply chains until Covid 19. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. If another global crisis, whether it’s a public health crisis or whatever it might be, were to hit without warning next month, how much more ready are we than we were in 2019?

Jim Kruse (13:20):

That’s a tough question to answer, mainly because I don’t have insight to what all the individual players in this game are, are doing, but okay. I would say that it takes time to develop a response to any of these kind of situations. So I’m sure we’re not there yet. Uh-huh, <affirmative> people think, well, I can just move my shipping stuff from Oakland to Houston and it’ll just be overnight real easy. Which is not the case. It typically takes years to set up the receiving facility, the distribution facility, the people involved, the the agents that are required to make things happen and so forth. So people are doing that. They’re reconfiguring supply chains, they’re ordering a lot of equipment, a lot of equipment’s being ordered to help make sure that we don’t get stuck with things just sitting in parking lots and warehouses. But again, it takes time to do these things. And so I would say we’re probably another year away from saying, okay, now we’re in a better position than we were last time. That’s just my personal guess. It’s not based on cold hard facts, but if you just read what people are doing and read what people are reporting, that’s what it looks like.

Bernie Fette (14:21):

Okay. And again, before Covid 19, the only people who were really talking about supply chains were people like you — people who work in some field of shipping or distribution or logistics or in your case in research related to all of those different things. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>. And now it seems that great numbers of people feel comfortable mentioning supply chains anytime that we don’t get our stuff delivered to us as fast as we want to get it. Is that in any way perhaps a good thing, the fact that people are just talking about supply chains at all?

Jim Kruse (14:55):

Oh, I think that helps. Public awareness is always a good thing because then you appreciate some of the measures that are being taken and some of the difficulties public agencies have in providing infrastructure and some of the things that private players have to do to make their businesses operate. You begin to appreciate that. I get the biggest kick outta people blaming everything on the supply chain, though. Not everything that’s late getting here is because the supply chain was an issue.

Bernie Fette (15:18):

<laugh>, but Okay.

Jim Kruse (15:19):

But, but it has been more frequent than in the past. I’ll grant that.

Bernie Fette (15:22):

Yeah. Okay. Well while you’re on that topic, tell us about some of the other things that people can blame if they’re not gonna blame the supply chain.

Jim Kruse (15:28):

<laugh>. Well, again, maybe your order was mishandled by the, uh, person you placed the order with. Okay. Sometimes, I guess it is part of the supply chain, but one of the things we saw during the pandemic, and it’s happening again, is that producers in China and some of the Asian countries had a Covid outbreak. And so they just shut everything down. We’re not doing anything. Nobody’s gonna come to work. We’re just stopping. Well, when that happens, you can’t fulfill the order that somebody in the U.S. ordered. So that is a reason why things slow down. If China’s having a a hiccup, we’re gonna feel it over here at some point. Mm-hmm. <affirmative> it, it does affect us. So it, it is not always the supply chain itself, although I guess you would say the producers, the beginning of the supply chain. I think a lot of what we’re seeing too is that as people begin to reconfigure their way of sourcing their products and as buying habits continue to change, we’re going more toward this online shopping than we ever had before. Mm-hmm. <affirmative>, I think there’re just gonna have to be some time for people to get past the mistakes they make in trying to do these things and and learn how to do it better. And I think we’re seeing a lot of improvements just almost every month here is something new being tried that hasn’t been tried before. So what do you blame it on? Um, I dunno what you blame it on, but again, I don’t think the supply chain was broken, but you’re gonna have to allow more time if you don’t wanna pay more for it. And so that’s just the way things are.

Bernie Fette (16:50):

Yeah. Yeah. What sort of takeaways would you like to leave with anybody listening to this?

Jim Kruse (16:58):

One of the things that I’d like to point out is that ports across the country are breaking volume records constantly. 21 was a volume record, 22 is another volume record, 23 may be another one. So it’s not that ports are slacking or that the system is not working. They’re handling record volumes. But when a record volume means I grew 10 percent and people wanted 20 percent, you still got a problem. Right. So yeah, that’s kind of where that was. I always say ports are not slackers. They are getting the work done at record paces and record volumes. It’s just there has to be a balance between what they can handle and what they are handling. That’s the problem. I think the other thing I would point out is that here in Texas especially, ports are really the lifeblood of the economy. The tonnage handled in Texas ports is 25 percent of the nation’s total, the nation’s total. That includes California, New York, East Coast, West Coast, all that stuff.

Bernie Fette (17:52):

Wow.

Jim Kruse (17:52):

So it is the lifeblood. And with our oil industry and petrochemical industry here, the amount of cargo that’s just moving in and out is just mind boggling. Houston is the nation’s busiest port that handles more vessels per year than anybody else. We hear all these things about California and New York and Seattle, but Houston is the nation’s busiest port. It handles it over 8,000 ships a year call this port, divided by 365. And you can see it’s a lot of activity.

Bernie Fette (18:20):

<laugh>. Wow. Yeah. That is,

Jim Kruse (18:21):

That’s, and some of our ports are military outlets. Beaumont is the nation’s busiest military port for moving supplies overseas. And Corpus Christi does it, Port Arthur does it. So we’re a military strategic point. Just things like that. It’s, you know, Freeport is one of the nation’s largest exporters of liquified natural gas — LNG. Ports are the livelihood of the economy. If they’re not working, we’re gonna notice it one way or another. Maybe not immediately, maybe I won’t see it in a missed order, but I will see it in the availability of overall goods and the cost of living.

Bernie Fette (18:53):

And what you’re saying sounds similar to what other folks on this podcast have said before about other modes of transportation. It takes something going wrong before we sometimes realize how often things go right.

Jim Kruse (19:07):

<laugh>? Yes, that is true. You know, we always hear when the airplane goes down and people die, that’s just horrible. But when you consider the thousands of flights per day, yeah, it’s a pretty safe industry overall. And the same thing happens on the water. We only hear about it when something really bad happens. And I tell people, it’s probably a good thing. You never think about it because that means nothing bad’s happening. Plus, I’ve never been stopped by a barge on my way to work. I’ve never had a ship run into me on the highway. So you know, they’re kind of over there, out of outta sight, out of mind, leaving me alone, but getting the work done. And that’s always a good thing.

Bernie Fette (19:40):

Good point. Last question. What is it that motivates you to show up to work every day?

Jim Kruse (19:47):

I just think the maritime industry is a fascinating industry. It involves people from all over the world, literally all over the world. It’s a true international enterprise, and there are no two places where everything is done the same. It’s just everywhere you go, it’s a variation on the theme. New things have to be handled, new situations have to be addressed. It’s just a really fascinating industry in terms of the variety of things you can look at and the variety of people involved.

Bernie Fette (20:13):

And it looks like you’ve got no shortage of things to study in the future on this topic.

Jim Kruse (20:18):

Oh, things are evolving rapidly. That’s true. <laugh>.

Bernie Fette (20:21):

Yeah. Jim Kruse, an expert in waterborne freight movement and it’s many connections, doing research to help refine how people here and abroad get the stuff they need. Thank you for your time, Jim. This has been really enjoyable. Thanks for sharing your insights.

Jim Kruse (20:39):

My pleasure. Thank you.

Bernie Fette (20:42):

When people couldn’t go on vacations during the Covid 19 pandemic, many found other ways to use their money, and consumer spending jumped by 23 percent. So it’s no surprise that every link in the supply chains from manufacturing to shipping was stretched beyond routine limits. Shippers and logistics experts have learned much from the biggest public health crisis in a century, and they’re putting those lessons to good use in finding ways to minimize disruption if and when a similar disaster strikes. Again, thank you for listening. Please take just a minute to give us a review and subscribe and share this episode, and we hope you’ll join us again next time for a conversation with Tom Scullion, a pavement engineer and road doctor, taking a forensic approach to find the reasons why some roadways fail to last as long as they should. Thinking Transportation is a production of the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, a member of the Texas A&M University System. The show is edited and produced by Chris Pourteau. I’m your writer and host, Bernie Fette. Thanks again for listening. We’ll see you next time.