Episode Preview with TTI's Allan Rutter (audio, 40s):

Full Episode (audio):

Episode Detail

March 30, 2023Episode 54. Off the Rails, On the QT: Train derailments happen daily, though few grab our attention.

FEATURING: Allan Rutter

Major railroad disasters tend to produce major news headlines, but there are hundreds of derailments each year in America that we never hear about. Why is that?

About Our Guest

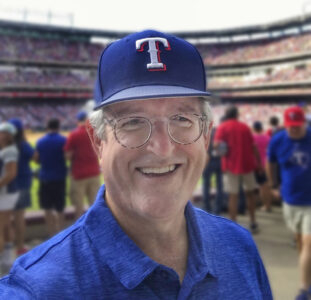

Allan Rutter

Senior Research Scientist

Allan Rutter is head of TTI's Freight and Investment Analysis Division and helps coordinate the Institute’s freight research practice. Allan led the U.S. Department of Transportation's Federal Railroad Administration for President George W. Bush from 2001 to 2004 and has also served as executive director of the North Texas Tollway Authority. Allan worked for four different Texas governors and was associated with the first iteration of high-speed rail in Texas in 1990.

Transcript

Bernie Fette (host) (00:14):

Hello. This is Thinking Transportation — conversations about how we get ourselves and the things we need from one place to another. I’m Bernie Fette with the Texas A&M Transportation Institute. The last decade has been the safest period on record for railroad transportation in America. Though you probably wouldn’t know that from reading news headlines in recent weeks. Nor would you know that according to the Association of American Railroads, the accident rate for the biggest railroads in America is at an all-time low — down by 49 percent since 2000. Here to help us understand a bit more about the current state of railroad safety is Allan Rutter, senior research scientist at TTI and the head of the agency’s Freight and Investment Analysis Division. He’s also a former administrator of the Federal Railroad Administration. And, he’s a returning guest on this show. Welcome back, Allan.

Allan Rutter (guest) (01:19):

Hi, Bernie.

Bernie Fette (01:21):

Okay, so train derailments have been in the news quite a bit lately. As you certainly know, from the many calls you’ve gotten from news organizations in recent weeks. And I’m not gonna go through an exhaustive list here, but just for a sample, we had the disaster in early February in the small town of East Palestine, Ohio. Crews had to let the toxic material burn off so that they could avoid an explosion. Then about 2,000 people were evacuated from their homes. Then another derailment in Ohio about a month later, followed by one in West Virginia, only a few days after that. And then in mid-March, two more in Arizona and Washington state with one of them spilling a few thousand gallons of diesel fuel. So according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, we have seen about 1,700 derailments over the past three decades. Every year. Why do these events keep happening?

Allan Rutter (02:18):

Well, one thing to remember about the number of derailments is most of those happen in rail yards at low speed. The vast majority of reportable train accidents is what the FRA continues to call ’em are in yards, not on mainline track. So it’s kinda like the distinction between having a wreck on the freeway and being hit in a parking lot at the grocery store. There’s a lot more grocery store crashes than there are freeway crashes when it comes to rail derailments. So that’s one thing is to remember that they’re not all high consequence. They’re not all the kinds of things that get on the news. I think the other thing that tends to happen, and I think has certainly happened after the East Palestine is it’s a little like when you’re looking for a car and you wanna buy a car and you’re thinking about, I wanna buy this type of pickup, and then suddenly you see that pickup everywhere on the road all over the place and in the parking lots. I think it’s a similar thing that there are derailments that are happening relatively frequently, but they get a lot more reported when they’re nearby a big high-profile one of those thousand derailments, and they’re a lot more train accidents than just derailments. The FRA, the Federal Road Administration, in keeping track of accidents also keeps track of accidents with certain levels of damage. There’s a reportable damage threshold that you have to report everything above like 50 or $60,000 or something. But they keep track of train accidents that have damage over a million dollars, and there’s about 60 to 70 of those on average for the past decade. Now, that could average to be about one a week. That’s about what we’re seeing now. And even then, not all of those are the same sort of high-profile things.

Bernie Fette (04:07):

One thing about the East Palestine incident, it very quickly became a highly politicized and divisive topic of discussion. And you could almost say that the accuracy of the story went off the rails along with part of the train. How do we make sure that we separate fact from fiction whenever these things happen?

Allan Rutter (04:29):

Part of that is the, the nature of what Congress gave the National Transportation Safety Board its particular job, which is when you have one of these high consequence, high-profile accidents within any mode of transportation, the NTSB goes out and starts investigating and they keep investigating. We probably won’t have a final report on East Palestine for 18 to 24 months. There again,

Bernie Fette (04:52):

It just takes that long.

Allan Rutter (04:54):

It takes that long. I mean, they’re looking at the 23rd rail car in this 149-car train is the first to derail because of a bearing problem around the wheel. They’ve got that whole truck assembly and it’s being sent to a lab, and they’re gonna look at all the metal behind it and how it got manufactured and how it’s been maintained over time. So they go down to the molecular level when it comes to materials. They’re also gonna spend a lot of time looking at the response and the hazmat handling of all that stuff.

Bernie Fette (05:26):

Is that typical in terms of how long an investigation takes for an incident of this magnitude that it’s 18 to 24 months? Just plan on it?

Allan Rutter (05:35):

Yep. Now, one of the things the NTSB has said in in response to this, given the profile of it, is that they’re gonna actually hold a field hearing to take some additional testimony and to talk about it in Ohio sometime in the spring as they’re getting their work done. But generally speaking, they, they will have a meeting to discuss the results of their investigation at that sort of 18 months timeframe. So one thing is the impetus to want to have hot takes about it exceeds the amount of actual factual information you have at your hand. That hasn’t kept people from talking about it as if they know what they’re talking about. I think the other thing is that sometimes, uh, and this is not a rarity, particularly in our polarized times, people see what they wanna see. There’s a little bit of sort of confirmation bias and or if you’re in the hammer business, all you see is nails. And so that’s, a lot of people have looked at this and said, well, this is clearly a result of the previous administration doing something to do away with a regulation. It’s like, well, actually, that regulation has nothing to do with this particular type of train and probably wouldn’t have had anything to do with the cause of the train accident, but there’s too much to be gained out of finger pointing.

Bernie Fette (06:56):

Right. And for some, they’re just not going to let facts get in the way of their narrative, it seems.

Allan Rutter (07:02):

Yeah. And one of those unfortunate things is for the thousands of people who were forced to evacuate their homes and farms mm-hmm. <affirmative>, all the finger pointing doesn’t do anything to help them. It doesn’t resolve their particular issues. And the amount of invective and unfounded certainty that comes out of a lot of people really doesn’t help them get to a point of, why’d this happen and how do I get back to feeling safe about being in my property? Those people are still suffering.

Bernie Fette (07:35):

Let’s talk about safety a little more broadly for just a minute. You and I and everybody out there on the highways, we are required to get a safety inspection on the cars that we drive every year. Does the rail industry have a similar requirement?

Allan Rutter (07:51):

Yes, they do. And there are all kinds of layers of those kinds of safety inspections. The railroads themselves have extensive operating codes or operating rule books, just because as we saw in East Palestine, when something goes wrong, it goes catastrophically wrong. So there are all kinds of reasons why you want to have clear expectations about how we’re gonna run our railroad. Here’s what everybody needs to expect from each other to maintain a safe operation. So the railroads have themselves a fairly extensive set of expectations and rules. There are kind of different safety disciplines on the railroads. There’s track — what goes into it, making sure that the rails are the right spacing and that those get maintained to a certain standard. There’s operating practices, you know, making sure that the crews will follow signals and will do the kinds of things that the dispatchers expect them to do. There are mechanical and operating procedures such as this derailment in Ohio comes about because of a bearing overheating that seizes up and causes the car to crash and with it the rest of the train. So the railroads themselves have all kinds of expectations and fairly extensive people that go out and do this job and lots of technology that helps ’em do that job. On top of that, you have the Federal Railroad Administration, which is a regulatory body that has a series of its own regulations, and they have a set of 400 or 500 safety inspectors all across the country in those same disciplines looking after, leveraging all this activity that happens on the rail side. So there’s an awful lot of attention that goes into making sure that all the elements of having a safe railroad are doing what everybody expects them to do. I think one of the things the NTSB is gonna be looking at in this particular issue about this privately-owned hopper car with plastic pellets in it, is what’s the maintenance record look like on that car for the last year or two? How has it been maintained? How was it that it failed so spectacularly so quickly? So there’s an awful lot of practices, responsibilities, and technology that goes into keeping railroads safe.

Bernie Fette (10:14):

And you mentioned the Federal Railroad Administration. You were the administrator of that regulatory agency in the U.S. Government for a few years, couple of decades ago, and you had many years in other parts of the transportation policy world before that. So you have seen railroad safety through multiple lenses. I’m wondering, how would you describe the typical conversations or interactions that happen between the FRA and the rail industry when major disasters happen?

Allan Rutter (10:48):

Part of that is a matter of how well you continue to maintain those relationships and the communication before you have one of those kinds of disasters. Uh, the ability to have an honest, open conversation about what’s going on really depends on you having a relationship to begin with. So. Part of each of those class one CEOs they have, and one of their responsibilities is to maintain a relationship with the regulators, both the economic regulators at the Surface Transportation Board and the safety folks at the FRA.

Bernie Fette (11:21):

And you mentioned class one CEOs, I guess those, uh, you’re talking about the, the big few rail companies in the United States.

Allan Rutter (11:29):

Yes. That is a nomenclature that stems from the Surface Transportation Board’s classification of rail. Do you meet a certain revenue threshold? Today, there are seven class one railroads in the United States. By April there will be six because Kansas City Southern and Canadian Pacific have been cleared to combine and will be the Canadian Pacific Kansas City Railroad. So those bigger guys who control most of the rail traffic, those are the folks that you’d want to have that kind of conversation. But yet, to get to your point, what happens in that room when you have that conversation? It needs to be data-driven. It needs to be about how is what just happened an anomaly? Is it a trend? Is there something going on that we need to pay attention to? The second thing is, what is it that you as a person responsible for railroad, what are you doing about it? And then what is it that the regulatory agency can do to help advance, leverage, make sure that that kind of activity continues to take place. Sometimes those conversations are tough ones because the railroad may not see things the same way the regulators do and or they have some issues between management and labor having different perspectives. But generally speaking, the ability to have that direct, honest and data-driven conversation is what’s gonna get to the bottom of how do we continue to make progress in making rail safe.

Bernie Fette (13:01):

Well, and I guess one of the reasons, correct, me here if I’m reaching, but one of the reasons that those conversations might be uncomfortable is that the more that is spent on safety can eat into profits. Am I oversimplifying there and is that one of the reasons that some of those conversations can be challenging?

Allan Rutter (13:19):

No, not necessarily. I, I think having a safe railroad is really incredibly important part of having a successful railroad. A railroad’s ability to make money depends on them having free, clear, safe operations. When you have something like what happened in East Palestine for Norfolk Southern, not only does that line, you know, it took three or four days for them to get traffic on it again, but tens of millions of dollars that have already been spent to remediate it and will likely continue to be spent in terms of the sort of accident industrial insurance, uh, trial lawyer complex, that that comes in afterwards. So the, the railroad has incredible direct financial incentives to make their operations as safe as possible, and it requires an awful lot of money to operate safely. Mm-hmm. <affirmative> railroads are incredibly capital intensive. They spend an awful lot more of their revenues than most other industrial industries, like the customers they serve in chemicals or motor vehicle manufacturing, railroads are putting a lot more of their revenues back into their capital network in large part because that’s the kind of thing they have to do to make sure that they can make money.

Bernie Fette (14:33):

Taking into account what we’ve talked about up to this point today, where would you say we are in terms of railroad safety overall in the United States, broadly speaking?

Allan Rutter (14:46):

I think generally speaking, if you look at it over a course of a couple of decades, all metrics of safety have been improving. Train accidents, particularly if you look at rates of accidents, rates of injuries, rates of fatalities, a lot of those numbers have been coming down. I think it’s also fair to say that, you know, things have sort of plateaued at a lower part of that curve for the last four or five years. So the need to, or the sort of impetus to make the next break in continuing to push the curve downward, there are probably gonna need to be some additional investments or additional breakthroughs to make that happen. But generally speaking, railroads have been making real substantial inroads and safety. The other thing that I think people need to understand is that when FRA looks at those consequences or measures of safety, if you think about fatalities that are rail-related, 90 percent of those fatalities are grade crossing crashes, and those are people in cars, or they’re trespass or pedestrian incidents with people being struck on the train right-of-way. It’s not necessarily railroad employees or the people that are being affected by some of these rail accidents.

Bernie Fette (16:00):

Right. And a lot of the news of, of events, like the ones we’re talking about, tend to be focused on what the trains are carrying. And they’re carrying to be more specific toxic hazardous chemicals. But is it not true that rail is still statistically the safest way to move those products?

Allan Rutter (16:21):

Between railroads, pipelines, and barges, those are probably your safest ways of getting some of these chemicals to different places. Pipeline network really requires a certain amount of bulk of those materials to be moved before you can make those kinds of investments. But you know, there’s an awful lot of oil and natural gas that gets moved by pipeline and moved in large amounts, long distances and done so safely. The alternative that you might think about in, if it’s not in a rail car, which has been designed to withstand rail crash forces, then it would be in a tank car, in a truck, uh, on the highway next to you. So I think generally speaking, that movement of those volumes of hazardous materials, it’s a better place to have them moving by rail than by some other mode.

Bernie Fette (17:16):

Right. And we need to move those materials one way or another, right? Because we, consumers, depend upon certain products like plastics in living our daily lives. And those products are made in part from the chemicals that the trains are hauling or those semi-trucks are hauling.

Allan Rutter (17:34):

Very much so. Railroads. And frankly, if you’re a motor carrier, uh, somebody who operates a truck fleet, you have legal common carrier obligations that if somebody has something, and in some cases, you know, 60 percent of the rail cars that are out on the rail network in general are owned by the private shipper themselves, not by the railroad. The railroads are obligated to offer service to that shipper. There’s a question about price and a question about service levels, but they don’t get to say, “Gee, that’s a really nasty chemical. I’m really uncomfortable carrying that. I’d rather not.” So if that material is in a vessel that’s been manufactured and maintained to certain federal standards, the railroad is obligated to take that. And it’s incumbent on everybody — the shippers themselves, the manufacturers of those rail cars and the railroads — everybody to do what’s mandated and set out in safety regulations to make sure that that happens safely. So that’s the first thing. Second thing is, you’re right, those chemicals are being moved because they’re being taken to someplace because somebody’s gonna make something with it, or there’s a process, an industrial process. They’re still an awful lot of coal that gets carried on. Uh, the rail network in general, they’re still coalfire utility plants. There’s some toxic biannulation chemicals like chlorine, which is used in drinking water. So there’s an awful lot of things that we depend on that really requires some of those chemicals to be moved.

Bernie Fette (19:08):

A few months ago, you and I on this podcast had a conversation about the rail strike that was just barely averted just before Christmas, but the two sides continue to have differences. Do you expect these recent high-profile derailments to have any impact at all on the ongoing discussions between labor and management in the rail industry?

Allan Rutter (19:35):

I’d say there are probably two things to note about that. One is the fact that there have been, as was talked about in the strike itself, a number of class one railroads have come to terms with different unions about sick leave, additional sick leave days they can have and take. It’s happening union by union, railroad by railroad. But there’s been an awful lot of movement across the board that’s been happening since the strike was averted in December. Since December, a number of class one railroads have reached agreements with individual unions, and there’s 13 of them and seven railroads. So that’s an awful lot of agreements that have to be reached. But a number of large railroads have reached agreements with large unions to have additional sick days and additional sick leave, which was one of the big high-profile issues in the strike. So some of that is being resolved as part of the overall collective bargaining process. That being said, the ability to make progress collectively on safety between rail labor and rail management is gonna be complicated by the relationships that were frayed during those months of tough negotiations. And I think each of the class one CEOs really have to find ways of bridging and healing some of those divides so that continued progress can be made on safety. It’s hard to have a collective conversation about keeping rail labor folks safe out on the roads if there’s a lack of trust. And so building that trust is gonna have to happen in the aftermath of that strike conversation.

Bernie Fette (21:21):

Much like the relationships that you were talking about between the industry and the Federal Railroad Administration a few minutes ago, right?

Allan Rutter (21:29):

Yes. But I think the railroads and the union folks at the same time have common interest in making sure that things are safe for the folks.

Bernie Fette (21:39):

Okay. Let’s turn to research as we start to wrap up here. From a research perspective, what do you think are the biggest one or two questions that scientists like you should be trying to answer in the interest of maintaining, improving railroad freight transportation and safer passenger rail safety as well?

Allan Rutter (22:00):

There been an awful lot of advances made in technology, particularly wayside technology. This is sensors and devices that are along the rail right of way pointed at the trains as they go by. There are cameras, there’s infrared, there’s temperature gauges, there are audio things that listen for the wheel rail interaction and detect if there’s a wheel metal problem. So there’s an awful lot of activity that’s been done on pointing devices at the cars as they go by. I think the next phase, and there are already a number of people doing some really important research on this, is how do we have more instrumented cars themselves so that not only can shippers know where their stuff is, but know under what conditions and what’s the real time performance of those cars as they’re out on the railroad. There’s a joint venture called rail pulse that’s being done by a couple of class one railroads, a couple of manufacturers of rail cars, and some technology firms that are looking to provide a sort of open source technology platform that it allows for shippers and manufacturers to put together instrumentation to have the cars themselves tell the story about how well they’re doing. I think that’s a really interesting and and high outcome area of research that a lot of people are investing an awful lot of money in.

Bernie Fette (23:32):

So we could see a lot of payoff just in terms of safety from those particular questions you’re talking about.

Allan Rutter (23:39):

Yeah. And there have been an awful lot of people who sort of are in that space who have also taken advantage of some of these incidents to say, you know, I’ve got an idea on something that would help with that kind of thing. So I think there’s an awful lot of opportunity to have additional safety gained by the rail cars themselves, pushing out a lot more information about how well they’re doing in the same way that our cars are pumping out information to the cloud, to the manufacturers to tell how well our car is performing.

Bernie Fette (24:12):

Continuing that exploration — is, is that what keeps you showing up for work every day?

Allan Rutter (24:18):

Absolutely. I mean, it’s uh,

Bernie Fette (24:19):

What else? What else keeps you showing up to work every day?

Allan Rutter (24:22):

I think the biggest thing that motivates me is the opportunity to work with the people both at TTI that I get to be alongside of in my 30 or 40 years of my professional life. I’ve had the opportunity to work with lots of really smart people, and that’s the big motivator for me. And the fact that we get to work with a lot of sponsors who are interested in doing some clever, innovative things — that makes working here at TTI very, very rewarding, and that’s why I enjoy showing up.

Bernie Fette (24:55):

We’re glad that you do, and also really glad that you could share some of your time and insight with us today. Allan Rutter, senior research scientist at TTI and former administrator at the Federal Railroad Administration. Thanks very much, Allan.

Allan Rutter (25:13):

Thanks for the opportunity, Bernie. It was a pleasure.

Bernie Fette (25:18):

The first railroad in North America was chartered almost 200 years ago. By 1850, more than 9,000 miles of track had been installed as much as the total mileage in the rest of the world combined. Since that time, rail transportation has been central to U.S. History, and to some extent we sometimes take it for granted. We hardly think about trains unless something goes wrong, something like a catastrophic derailment. But the news of major derailments in early 2023 runs counter to the actual record. More than 99 percent of all hazardous material moved by rail reaches its destination without any problems. It’s that kind of performance that’s made railroads the safest way to move goods over land. Thanks for listening. Please take just a minute to give us a review, subscribe and share this episode, and we hope you’ll be back next time. Thinking Transportation is a production of the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, a member of the Texas A&M University System. The show is edited and produced by Chris Pourteau. I’m your writer and host, Bernie Fette. Thanks again for listening. We’ll see you next time.