Thinking Transportation

Engaging conversations about transportation innovations

Thinking Transportation Podcast

Episode 8. Hey, Where’s My Amazon Order? Promises of super-fast delivery are straining our transportation system.

The pandemic and a record-setting holiday shopping season made 2020 a year like no other for the freight and delivery industry. TTI Senior Research Engineer Bill Eisele helps us understand how clicking Next Day Delivery or Same Day Delivery directly impacts (and imposes lasting consequences on) our transportation network.

Episode Preview

Full Episode

About Our

Guests

-

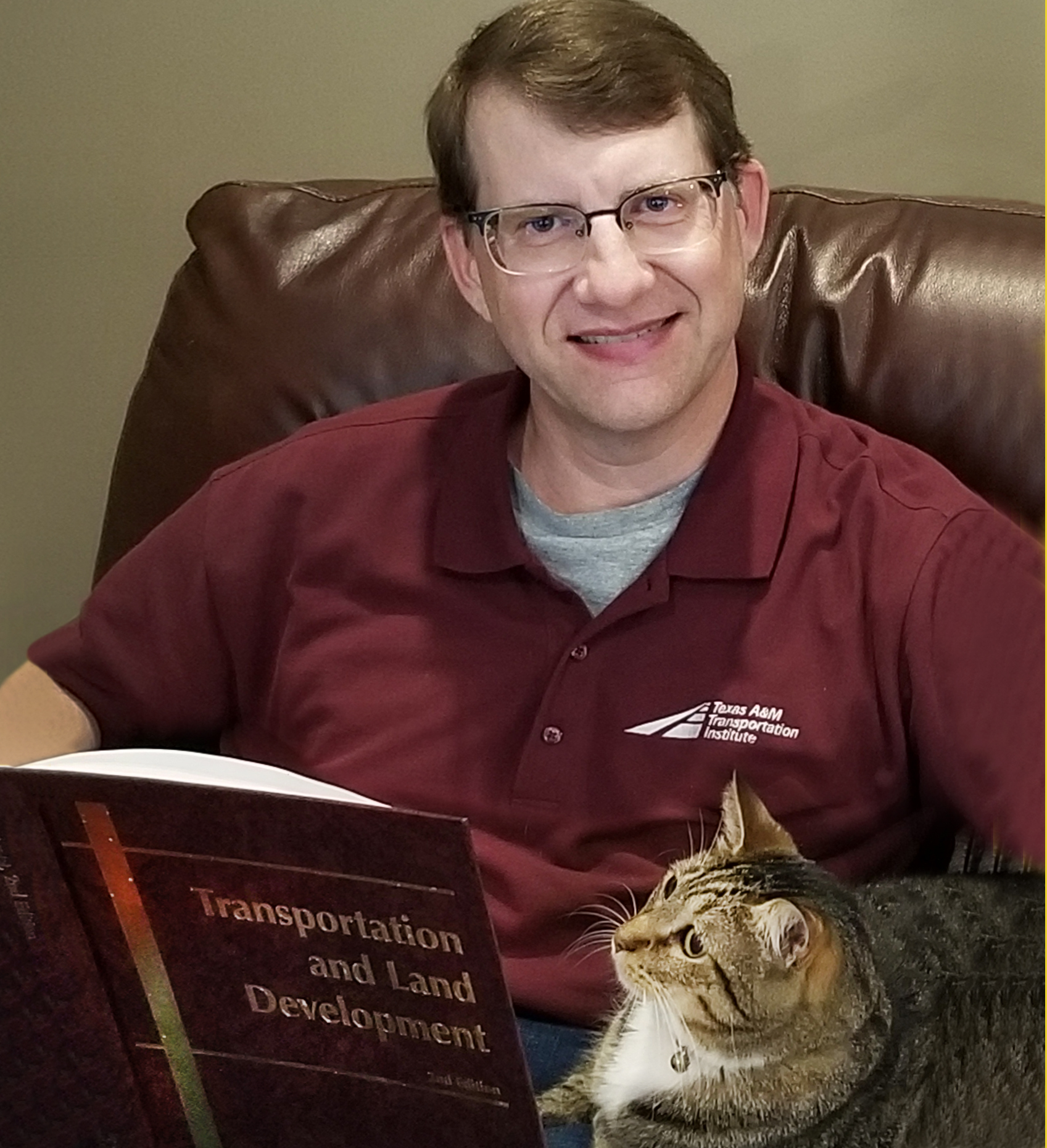

Bill Eisele

Senior Research Engineer

TTI Senior Research Engineer Bill Eisele leads TTI’s Mobility Division. He is an expert in the areas of mobility analysis, performance management, freight mobility, urban freight transportation and access management. For more than 25 years, he’s performed research for a variety of industry and public-agency sponsors.

Transcript

Bernie Fette (host) (00:14):

Hello. Welcome to Thinking Transportation — conversations about how we get ourselves and what we need from one place to another. I’m Bernie Fette with the Texas A&M Transportation Institute.

Bernie Fette (00:26):

Remember when special delivery was a thing? Long before FedEx or Amazon, if you paid extra postage, whatever you mailed or whatever was mailed to you was given a higher priority than standard mail. Your delivery was special, for the right price. Fast-forward to now. With a single mouse click, we get deliveries faster than ever, sometimes only hours after we place the order. But, that same-day/next-day fix that we’ve come to expect is taking a toll on our transportation system. Our guest, Bill Eisele, is here to help us understand more about that. Bill is a senior research engineer at TTI. He’s been studying mobility issues for more than 25 years, focusing a lot on the mobility of freight. In other words, he studies how the stuff that you buy gets from the factories to the store shelves or to your doorstep. Welcome, Bill. Thanks for being here.

Bill Eisele (guest) (01:39):

Absolutely, Bernie. Thanks for having me. Looking forward to it.

Bernie Fette (01:43):

To begin, I’d like to revisit an experience that many of us have had. Let’s say that we shipped a holiday package early and it still got there late. And even apart from holidays, next-day delivery often turned into next-week delay. Is it fair for me to curse the delivery service or the shipper, or is it more complicated than that?

Bill Eisele (02:09):

Well, I’ll tell you Bernie, if cursing is your coping mechanism, I guess that would be acceptable; but honestly you can probably cast a wider net to your recipients of your cursing, because you’re exactly right. It’s much more complicated than that. There’s many moving parts that are involved with this delivery supply chain and really a breakdown anywhere can cause a missed delivery. If you think about it, there has to be a correct order processing. They have to pull the right inventory. They have to select a carrier. They have to put that product on the right route and avoid the congestion and they have to find a place to park. There’s just so many places along that line where things can break down.

Bernie Fette (02:51):

And that’s why they call it a supply chain, right? Because it’s only as strong as its weakest link?

Bill Eisele (02:56):

Absolutely. That’s a fantastic analogy, and it really is a chain. And I think oftentimes we forget the depth of that back chain that leads up to that person who’s standing at our front door. There’s supply chains that are across different modes. You may not think about it, but when you buy some little widget off of Amazon, there could be vessels on the other side of the planet that are moving around to move that product to you. It’s, it’s a really large global landscape.

Bernie Fette (03:30):

Yeah. Really complex, as last year really went a long way in demonstrating for us. Has 2020 come to represent our new normal in the freight and delivery world?

Bill Eisele (03:43):

Well, 2020 and now even 2021 has really impacted everything. We all know that. Generally speaking, in a lot of places, the vehicular travel dipped probably 50 to 60 percent due to the pandemic. And it has generally rebounded, but still probably 10 to 20 percent below what we were seeing before the COVID hit. But freight tells a different story. On the other hand, it dipped some, but is maybe now 5, 10 percent higher than the pre-COVID levels. And we generally see that; that we’ve seen that while there really hasn’t been a whole lot of drop-off in freight. And actually there’s been a bit of an uptick because we’ve been using that as a way to get our products and services.

Bernie Fette (04:26):

Right. Did people who study freight like you do, did you kind of see that contrast coming? The sharp contrast between personal travel dropping so much that freight, you know, actually notching up a little bit. Did you see that coming?

Bill Eisele (04:40):

It was certainly no surprise. There’s tremendous growth in e-commerce anyway. And for that to stop suddenly when everybody is now — even new markets, new people that have never used it before — are starting to suddenly have more deliveries shipped to them, their groceries sent to them. And different demographics have started to do it. You know, more elderly individuals who had never really thought about doing that or, or were in situations where gee, I have to get my groceries brought to me, or I don’t have any other options. And so there’s more and more truck traffic that was generated.

Bernie Fette (05:19):

You and I talked a few weeks back about the roadway system as a big funnel. That seems like a really helpful illustration. So for people listening, what does that illustration look like? And has the past year changed how that funnel looks?

Bill Eisele (05:39):

Yeah, that’s really a good analogy for people to try to get a handle of what this looks like. So if you think about the roadway system as a big funnel and think about pouring rice into that funnel, rather slowly, it flows through and there really isn’t any problem. But if you pour it very quickly, it can lock up. That might be increased traffic. And therefore, you know, you have some sort of bottleneck. The reality is, is suddenly we’ve got more trucks doing more routes, perhaps routes we didn’t anticipate, and our system really wasn’t prepared for.

Bernie Fette (06:15):

So did you notice in 2020, even as freight and delivery trips were increasing, generally speaking, what happened to the congestion levels for those delivery trips?

Bill Eisele (06:28):

It’s kind of interesting that suddenly the road was freed up, right? So there’s more trucks that are out there and deliveries being made. But as we observed watching the news, you could flip it on in the evening and look, and they would be showing the roads without a whole lot of traffic on them. So what we saw is that in some ways it was easier for some of those trucks to get around on the system. Sure, they had maybe their own inherent bottlenecks or maybe they were faced with what they always are faced with, like curves or hills that always have slowed them down. But in terms of the amount of traffic around them, it was a little bit easier on those truck drivers maneuvering on the system.

Bernie Fette (07:12):

And that’s on the roadways, but you mentioned that there are other opportunities for bottlenecks. Those would be at the loading docks, what they call fulfillment centers. Did you notice any sort of trends in bottlenecks in those areas?

Bill Eisele (07:26):

Yeah. With, you know, fulfillment centers, distribution centers, these are locations where the product is actually collected, organized by the carriers and then shipped out. So that’s where, when you put your order in, they’re the ones that are picking it off of their shelves in their buildings, and then putting it on the trucks to make the run. And that’s a good point. What they observed was just so much demand on these fulfillment centers and distribution centers and getting that product out. These people have to make the deliveries as promised. So what are they going to do? If the distribution centers aren’t adequate, they made need to build more. They may need to move them closer to the urban centers where the demand is. They may have to actually put more assets out on the road if they have a higher demand, just meaning more trucks, sending out more trucks.

Bernie Fette (08:21):

Well, if part of the answer is building more distribution centers to meet the demand — and if freight and delivery services are more likely to encounter bottlenecks at distribution centers as seemed to happen in 2020 — how do they react to those bottlenecks whenever they can’t just build a distribution center overnight?

Bill Eisele (08:43):

It is a challenge for them. And that’s essentially what they’re always struggling with. You know, the way they get an edge over their competition is whoever kind of figures out the system that’s out there now and how to get the deliveries to their customers most efficiently, effectively, safely, is going to win. And so they’re constantly looking at algorithms that look at the best way to make those shipments, make their delivery times and work around those known bottlenecks.

Bernie Fette (09:12):

So I don’t want to hang too much on the 2020 question, but was 2020 an anomaly in terms of the freight and delivery business?

Bill Eisele (09:23):

Was 2020 an anomaly in the freight and delivery business? Probably. In the last hundred years, we hadn’t faced anything like that, and I hope we don’t so suddenly face anything like that again. But what it does bring to light is it helped us all to have the conversation with people that are probably not used to thinking about how their goods get to them, and really just how extensive and fragile our transportation system is. So is it an anomaly? I think we’ve all been in the public sector, working and aware of some of these issues, trying to create these efficiencies in the transportation system. I sure hope we get out of this one soon, but it does certainly shine a light on the fact that there are some things that we need to fix, and without addressing some of these issues, we could continue to face some of these challenges in our supply chains, challenges with bottlenecks on the roadways without proper investment.

Bernie Fette (10:29):

Are the current trends that we’re seeing giving us any clues about the future? Should we expect the next couple of years to be much different from what we’ve recently experienced?

Bill Eisele (10:41):

Yeah, I think we’re getting some clues. We’re probably getting even more questions. We know people are going to continue to travel. We know that people will continue to need stuff. But think about this: Before the pandemic really hit, predicting the future was tough enough. Now it’s increasingly difficult because we have to think about how are people going to travel when, where, because of this incredible change in behavior that’s coming about, we’re all thinking more about the trips we make. Do we need to make those trips? When do we make those trips? And once that sort of settles down and we get sort of used to this new normal as a society, then we can start having the question about given where people have settled in to their homework, recreational life. Now, how do we best get goods to them? So I’m afraid at some level, we’re going to continue to have some of these questions come up that we’re going to have to keep addressing.

Bernie Fette (11:41):

And anytime we talk about transportation challenges in most conversations, technology gets brought up as a potential area of solutions in the context of freight and delivery. And that would be perhaps autonomous deliveries, drone deliveries? To what extent do you think technology fits into the solution mix in the near term?

Bill Eisele (12:05):

Technology certainly plays into the solution mix. And it always will. How near term it will be, is probably the better question. Autonomous delivery is coming. I think it’s probably a little bit of a ways off. We’re already seeing some of the technology in our own personal vehicles that help us to be more connected to the infrastructure. You know, brake assist, lane corrections, et cetera. So, those are some of the early steps to this autonomy that I think is coming. But I really think that as we have more and more innovation in the goods movement, that that’s going to get us more prepared for more general automation and in other places. So, some of the last-mile goods movement, those are nice controlled environments to begin to work with this technology. You mentioned drones. There’s some immediate obstacles with, with drones related to airspace regulations, noise, privacy, but there’s big investments being made. Amazon has patents on moving trains being used at these fulfillment centers and even airborne fulfillment centers that use unmanned aerial vehicles for delivery. So certainly, private industry is investing and they’re seeing drones as part of the future. The bottom line with all of that is the technologies will take hold if they can be proven safely and reliably to reduce time and costs for those deliveries.

Bernie Fette (13:39):

On the topic of technology, not too long ago, we were discussing in another episode self-driving cars. And it sounds a little like you’re voicing a very similar expectation as Bob Brydia did about how there may be a lot of promise, but it’s not something that necessarily we’re going to see right away. One example that comes to mind for me is some of the work that TTI has done in the area of truck platooning, which meets at that intersection of self-driving technology and freight. Does that possibility hold a lot of promise and, or are there other areas that you think also hold promise that we might see sooner rather than later?

Bill Eisele (14:17):

Yeah, I think it does hold a lot of promise. And as Bob alluded to then I, I really do see the self-driving vehicles for moving goods a lot sooner than for moving people. And we’ll probably see that in the next decade, we’re already seeing some of that in controlled situations over the road applications. We’ll probably follow in the, in the following decade, but there’s been a lot of technology tests with automated vehicles for last-mile freight deliveries, robots, shuttles, other things of that sort. The long-haul trucking sector has already begun to really be leaders also in the self-driving trucks. So I really do think that that’s exactly right, that we’re going to see that innovation in freight in that particular market sort of test the waters for us as a society and as a technology, before we start to roll it out into a lot of other locations and places.

Bernie Fette (15:17):

What do you hope that people listening to this conversation would take away?

Bill Eisele (15:20):

That’s a great question. With this growth in e-commerce, the main thing would be when you’re at home, online shopping, I hope people understand the impact of activities like “add to cart” and “next day delivery.” And especially when they click on “same day delivery.” These choices have huge impacts on our global transportation system and our built natural environment. Manufacturing the goods that are being ordered, delivering them, uses all forms of transportation modes. We’ve mentioned that it’s trucks, it’s ships it’s even ocean-going vessels. So, in general, I hope people better appreciate this extensive supply chain and supply lines and the infrastructure that’s standing behind that poor lone delivery person who shows up at their door with their package. There’s just a whole lot more to it.

Bernie Fette (16:16):

Whenever we have that website open and we’re placing that order, and there’s a big flashing banner that says, “free next-day delivery” or “free same-day delivery,” in reality, that free delivery isn’t really free.

Bill Eisele (16:33):

That’s exactly right. That’s a great pickup, Bernie, it might feel free to you — next-day, free shipping. There’s always a cost and that cost, you may not feel that cost right then in your pocketbook, but we’re all going to, as a society, pay for the impacts of that. It may be environmental impacts. It could be impacts on the climate. It could be impacts in what we’re producing with all this packaging and plastics and things that are being produced. And of course, we talked about the distribution centers, fulfillment centers, the land use that’s impacted, not to mention just the bottlenecks on the system from all the traffic. So there’s a great need, and there’s something that we can all do to kind of chip in and be aware of this. And then certainly we’re going to need more investment in the infrastructure. You know, obviously a good strong freight network is critical for our economic vitality. So we’re going to have to have adequate investment. That’s critical.

Bernie Fette (17:37):

So what I think I hear you saying, Bill, is that whenever we click, yes, please deliver it free tomorrow, the benefit we enjoy is pretty immediate, but the consequence of that choice is delayed. And so it’s not going to be something that we notice until much later, whenever the consequences appear in the form of more infrastructure deterioration or more bottlenecks.

Bill Eisele (18:02):

That’s a really good summary, Bernie, of that; yeah, it’s, our gratification is immediate to get that widget in our hand by the next day. But there’s a lot of things going on behind the scenes that we need to be aware of. And quite honestly, that’s going to catch up with us in both the natural and built environments.

Bernie Fette (18:21):

Just one more thing, Bill. Why do you do the work that you do?

Bill Eisele (18:25):

Why do I do what I do? I really enjoy it. It’s a lot of fun doing the work. I enjoy tackling these very complex societal impacts that we have in the transportation field. I don’t know of another field that allows us to get involved with something that we all feel so intimate about and can get so emotionally attached to as transportation, if we’re reliant on our automobile and it goes down, man, that really throws us off and we all get so frustrated when we’re stuck in congestion. If you think about trips and trip making and transportation, some of our best memories have to do with transportation and taking vacations and things of that sort. It’s also very critical for us. We have very important trips we need to take. We have to get to a doctor. We have to get to the daycare to pick up our kid. So it can quickly become something that we can all get emotionally attached to. And so it’s fun. We get to solve challenging problems. We have a lot of different aspects of things that are involved and a lot of stakeholders that are involved. And I really enjoy that process of, of noodling through those solutions and providing a way to help public sector agencies do that.

Bernie Fette (19:51):

Bill Eisele, senior research engineer at TTI. Thanks so much for sharing your insights, Bill. We really appreciate it.

Bill Eisele (20:00):

Thanks for the opportunity, Bernie. I really enjoyed it.

Bernie Fette (20:04):

The competition for road space, for both travelers and shippers, has been getting more intense every year. To avoid crowds, lots of us opted for more home delivery instead of in-store shopping for items as everyday as cereal and toilet paper. And then, online holiday sales set a new record, jumping by more than 30 percent over 2019. Altogether, 2020 was not exactly a routine year in the freight and delivery business. Whether 2021 will be much different is anyone’s guess. One thing is certain, though. Every time we click on “next-day delivery” or “same day delivery,” our online shopping habits show how they have far reaching implications for our roadway system.

Bernie Fette (20:57):

Thanks for listening. We hope that you’ll subscribe and share and we hope you’ll check in with us again next time, when we talk with Mike Manser, a senior research scientist at TTI. Mike will help us understand why motorcycle crash fatalities across America add up to around 5,000 every year — even as overall roadway deaths have declined.

Bernie Fette (21:20):

Thinking Transportation is a production of the Texas A&M Transportation Institute, a member of the Texas A&M University System. The show is edited and produced by Chris Pourteau. I’m your writer and host, Bernie Fette. Thanks again for listening. See you next time.

Latest EPISODES

Your

host

Allan Rutter

Senior Research Scientist

Allan Rutter manages TTI’s Freight Analysis Program and is the new host and writer for Thinking Transportation. Affiliated with TTI for 10 years, Allan has more than 35 years’ experience in transportation, mainly in the public sector in Texas. More info on “Big Al” can be found in his TTI bio and at his LinkedIn page.

About

Engaging conversations about transportation innovations

Our ability to get from Point A to Point B is something lots of us take for granted. But transporting people and products across town or across the country every day is neither simple nor easy.

Join us as we explore the challenges on Thinking Transportation, a podcast about how we get ourselves — and the things we need — from one place to another. Every other week, an expert from the Texas A&M Transportation Institute or other special guest will help us dig deep on a wide range of topics.

Transportation has a profound impact on our daily existence. So, the conversations you’ll hear on Thinking Transportation are about more than just how we move about. Often, by extension, they’re also about how we live.

Email us at [email protected].